This unit develops students’ recognition of pattern (consistency) in equations involving multiplication and division with whole numbers.

- Describe and represent the commutative property of multiplication

- Describe and represent the distributive property of multiplication by attending to place value

- Recognise that multiplication and division are inverse operations, and interpret division as either equal sharing or measuring.

- Find relationships in the difference of perfect squares, e.g. 7 x 7 = 49 so 8 x 6 = 48.

This unit develops students’ recognition of pattern (consistency) in multiplication and division equations involving whole numbers. The patterns of pairs of equations embody important properties of multiplication and division, such as commutativity, distributivity, and inverse. Students learn to represent specific examples where the properties are used then provide convincing arguments about why the properties hold in all circumstances.

An important consequence is that students learn to consider variables as generalised numbers, and express relationships involving whole numbers under multiplication and division.

In this unit we build on research by Deborah Schifter, and colleagues, about the development of algebraic thinking. Shifter works for The Educational Development Centre, a non-profit research organisation in the USA. Her approach follows several steps that can be linked to ‘folding back’ in the Pirie-Kieren model of conceptual development, commonly used in New Zealand classrooms.

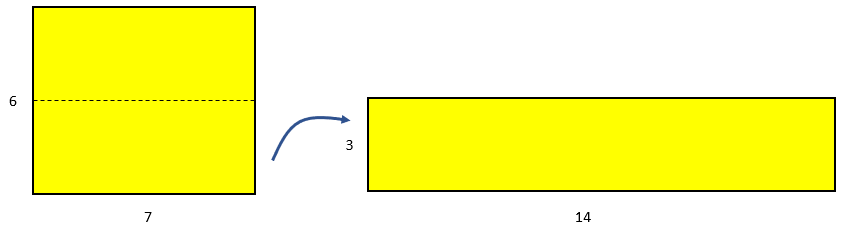

The phases of the approach are as follows:

In this unit, claims are developed through equation sets involving multiplication and division. The sets aim to develop students’ understandings of the properties of multiplication (commutativity, distributivity, associativity, identity and inverse). By expanding the equation sets to include division, students will learn how these properties hold, or do not hold, when the operation is changed.

The learning opportunities in this unit can be differentiated by providing or removing support to students and by varying the task requirements. The difficulty of tasks can be varied in many ways including:

- using physical objects to connect number and operational symbols, including equals, to transformations on quantities

- modelling mathematical procedures (e.g. showing multiplication and division using equal sets and arrays)

- encouraging students to work collaboratively in partnerships (mahi -tahi)

- allowing access to calculators to confirm answers and shift attention to why the patterns occur

- restricting the domain of numbers being investigated. For example, students might work at first with facts they know or are in their learning zone. Pushing examples beyond known facts can help students see the power of relationships they investigate, e.g. 12 x 33 is easier to solve as 4 x 99.

- providing helpful hints at ‘hidden’ locations around the room

- displaying the work of students as models for others

- providing formats for recording that scaffold a process.

The contexts for this unit are strictly mathematical but the materials used can be adapted. Physical items that have significance to your students might be better used than standard mathematical equipment. For example, if you have a big set of shells for environmental studies you might use those shells as the materials. Contexts may arise out of the preferred materials. Kaitiakitanga (guardianship over the environment) might be supported by finding clever ways to count the number of a particular animal or bird or pieces of rimurapa (seaweed) found in a section of the beach or parapare (barnacles) found attached to rocks at low tide. Whānaungatanga (family) values might involve finding fair and equitable ways to share shellfish that are harvested. Note that equal shares assumed in the operation of division are not always aligned to values of fair sharing.

Te reo Māori vocabulary terms such as ahuatanga koaro (commutative property), ahuatanga tohatoha (distributive property), koaro (inverse), whakawhanui (generalisations), tauwehe (factor) and otinga (product) could be introduced in this unit and used throughout other mathematical learning.

- Square tiles, connecting cubes

- Place value materials

- Calculators (optional)

- Square grid paper

- Copymaster 1

- PowerPoint 1

All lessons in this unit follow the same sequence of phases as given in the phase approach diagram shown. A poster of the phases is provided as Copymaster 1 for students to refer to. The notes suggest possible student ideas and teacher reactions to those responses. It is not feasible to anticipate all ideas students might give. Be flexible in how you respond to students, as opposed to focusing on teaching the sample ideas and representations provided.

PowerPoint 1 contains seven equation sets that drive the unit. The sets might form the basis of a week-long unit. The phases for each equation set are described below. The sets are labelled in the top left corner of each slide for reference.

Equation Pairs Set One

Slide one has the first pattern to look at. The pattern involves the commutative property, i.e. a x b = b x a, which students should be familiar with. It is used as an example to familiarise students with the approach.

- Noticing Regularity

Use ‘think, pair, share’ by inviting students to look independently at the four examples, work out the missing values, then share their ideas with a partner. In the class discussion expect students to express their observations in ways that are clear to others. Students should re-express their ideas if others do not understand what they are saying. You may need to remind students that the ‘something going on’ relates to all four examples, not just one. Expect responses like:

S: The numbers are just turned around, like 9 x 4 becomes 4 x 9.

T: Can you be more specific? Which numbers are turned around?

S: The numbers being multiplied each time.

Discussion opens the possibility of using correct mathematical terms, like factor (number being multiplied), and product (answer to multiplication).

S: The products (answers) are always the same.

T: All four patterns have the same product? What do you mean?

S: No. The products are the same when the factors are turned around.

- Articulating a claim

Encourage students to state a claim about what is going on with all four examples in Pattern One. Initially, they might do this individually, before working in small teams to refine their ideas and the way they express those ideas. Encourage the mahi tahi model where students work collaboratively. Potential ideas may include:

If the factors are the same, and you turn them around, the product doesn’t change.

The first factor changes places with the second factor. The product is the same.

Aim for students to express their claims in clear, minimal terms, using correct mathematical language. For example, ‘turning around’ is not as clear as 'order of the factors'. You could compare different statements from groups of students, to highlight the importance of such clear language. Links could be made here to explanation writing (i.e. the need to be clear, informative, and concise). - Representing

In this phase students choose representations to show why the pattern holds consistently. Students might choose physical manipulatives, such as linking cubes or counters, draw diagrams such as number lines or arrays, and use contexts from everyday life. Encourage students to begin with the first two examples of equation pairs then consider how the same relationships might generalise to the last, and other similar, equation pairs.

Examples might be:- I made 7 x 5 first using cubes. Then I took one cube off each group of five cubes to make one group of seven cubes. I found out I could make five stacks of seven cubes from the seven groups of five cubes.

- I drew 7 x 5 as an array. The fives were the columns. When I turned the array around the sevens became the columns, but the total number of cubes was the same.

- I made 7 x 5 first using cubes. Then I took one cube off each group of five cubes to make one group of seven cubes. I found out I could make five stacks of seven cubes from the seven groups of five cubes.

- Some representations are less helpful than others in terms of understanding the structure of the commutative property. For example, jumps on a number line do not show how each item in a set is used to form the new sets. It is important for students to recognise that repeated addition is not multiplication although they arrive at the same number. In New Zealand, when teaching multiplication, the multiplier is the first factor and the multiplicand is the second factor. Other countries teach in reverse so expect some students to be confused.

- Your questioning is important to support students in connecting symbols and other representations.

- Explain where the 7 and 5 are in your representation.

- If you start with 7 x 5, why can you only make five sets of seven?

- What do the 5 and 7 represent in 5 x 7?

- How does your representation show that the product stayed the same?

- Constructing an argument

In this phase students are asked to formalise their "noticing" by creating a statement that can be generalised to all cases. The discussion may start with a specific equation pair but must be extended to describe what occurs in general.

S: With 7 x 5, one from each five makes a set of seven. Because there are five in the sets that means exactly five sevens can be made.

T: So how does that work in the same way with 9 x 4, 8 x 99, and 5 x 36?

This might lead to expressing the property in general terms.

S: The first factor multiplied by the second factor has the same product as the second factor multiplied by the first factor.

T: If we gave names to the first and second factors, like a and b, could we express the property more simply?

Some students might experiment with algebraic notation such as a x b = c so b x a = c, or may use symbols (e.g. emojis) to simplify their thinking. Note that this represents the starting equation pairs. In general, "a sets of b" can be remodelled - meaning taking one object from each set of b creates sets of size, a. This can be done b times, resulting in b x a (b sets of a).

T: Do we need to say both equations have an answer of c? Do we need c?

S: We could just write a x b = b x a.

Focus on the class of numbers that have been used, i.e. whole numbers. Encourage students to investigate if the commutative property holds for integers and rational numbers, e.g. If ½ x 36 = 18 does 36 x ½ = 18.

Equation Pairs Set Two

Ask the students to approach the second equations set more independently. Consider the needs of your students - it may be more appropriate for you to work with small groups, and to organise students in small groups or pairs for these tasks. From this point each equation set is discussed succinctly using the phases of the approach.

- Noticing regularity

The four equations apply doubling and halving, thirding and trebling of the factors in the first equation. This strategy is sometimes called proportional adjustment since it underpins the concept of equivalent fractions. The completed sets should be:

8 x 3 = 24 6 x 10= 60

4 x 6 = 24 [Doubling 3, halving 8] 12 x 5 = 60 [Doubling 6, halving 10]

9 x 9 = 81 7 x 6 = 42

27 x 3 = 81 [Trebling 9, thirding 9] 14 x 3 = 42 [Doubling 7, halving 6]

- Articulating a claim

Expect students to use phrases from their conversational language, such as “when one number doubles, the other halves”. Introduce important vocabulary such as factor (i.e. all the numbers that evenly divide a whole number -3 and 2 are factors of 6) and product (i.e. the result obtained when the numbers are multiplies together). This will help to clarify what numbers are being referred to in the claims. If the claim is restricted to doubling and halving, draw attention to 9 x 9 = 81 and 27 x 3 = 81. The aim is to broaden the claim to the equivalent of “one factor is divided by a number, n, the other factor is multiplied by n. The product stays constant (the same).”

- Representation

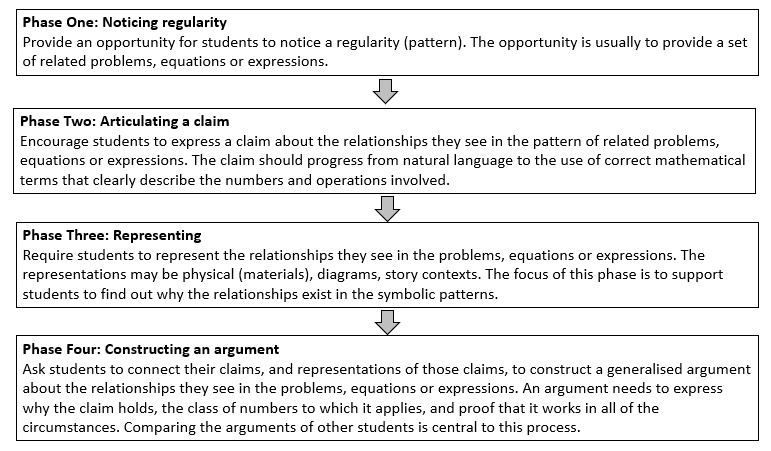

Expect both physical and diagrammatic representations to be used. A cube stack representation might look like this:

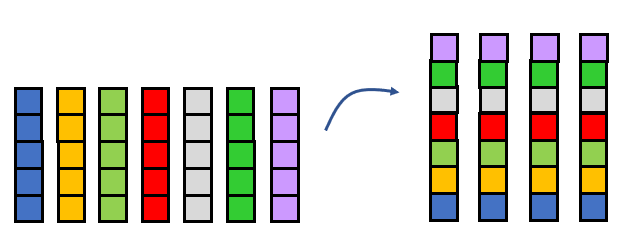

Diagrams of a ‘sets’ representation might look like this:

Arrays might also be used as a powerful representation. Initially cubes might be used as units of area leading to a more abstract use of side lengths.

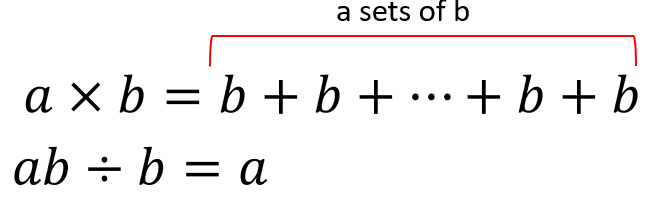

- Argumentation

Look for students to justify that a given quantity, say 24, can be created by multiplying two factors, say 4 x 6. Keeping our quantity constant, one factor can be divided in equal parts, say each 6 is divided into three equal parts (3 twos). Now there are three times more of those parts making up 24. The number of parts a factor is divided into is a variable. Some students may be comfortable with using a label, like n, to represent the number of equal parts. The factors and product are also variables and might be represented with shapes or letters. Although symbolic representation is restricted at this level, algebraically the relationship might be expressed as:

Look for students to generalise ‘undoing’ nature of the inverse operations, i.e. divided by n, multiplied by n. At this level students are progressing towards the use of letters to represent variables. You might also introduce the quotient interpretation of fractions, e.g. a÷n can be expressed as a/n. Multiplication can also be represented without the x symbol, e.g. a×b can be represented as ab.

Equation Pairs Set Three

- Noticing regularity

The four equations apply the distributive property. This property is used a lot in the multiplication of multi-digit numbers. The completed sets should be:

7 x 10 = 70 5 x 20= 100

7 x 11 = 77 [Adding 7 x 1] 5 x 22 = 110 [Adding 5 x 2]

9 x 50 = 450 6 x 100 = 600

9 x 53 = 477 [Adding 9 x 3] 6 x 105 = 630 [Adding 6 x 5]

- Articulating a claim

Expect students to use phrases from their conversational language, such as “adding on so many lots of the number”. Encourage students to use of mathematical vocabulary such as factor and product to clarify what numbers are being referred to in the claims. You may need to model this for students. Encourage clarity by asking questions like:

Can you know how much more the second product is than the first? How?

What does the first factor mean? What does the second factor mean?

The aim is to state the claim as something like “If a number is added to the second factor, then the product increases by the first factor multiplied by that number.”

- Representation

Expect both physical and diagrammatic representations to be used. Since most of the first equations involve multiples of ten or 100, place value blocks (MAB) might be useful.

Diagrams of tens and hundreds can be made schematic to highlight important structure.

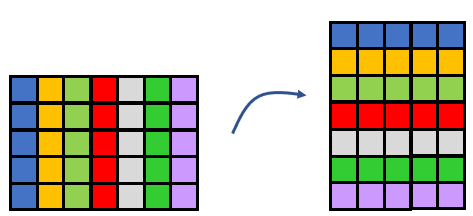

Arrays illustrate how the first factor ‘acts’ on the second factor as it is changed. - Argumentation

Look for students to justify that two factors multiply to a given product. The starting product might be expressed as a x b. Adding a number to b results in the second factor becoming b + n (n is the number being added). The product increases by a x n. It is important for students to consider what is happening with all four equation sets, in that n is a variable, and can be ‘any number.’ Students are working towards expressing relationships among variables using letters and equations. Progress can be encouraged by working with the notations that students develop themselves.

Algebraically the relationship might be expressed as:

a×b so a×(b+n)=(a×b)+(a×n)

Multiplication can also be represented without the x symbol, e.g. a×b can be represented as ab, and unnecessary brackets (due to order of operations) can be removed.

ab so a(b+n)=ab+an

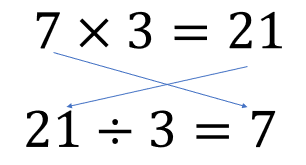

Equation Pairs Set Four

- Noticing regularity

The four equations apply the inverse relationship between multiplication and division. This property is used by students to solve division problems by measurement, e.g. “How many x’s go into y? The completed sets should be:

8 x 6 = 48 7 x 3 = 21

48 ÷ 6 = 8 [expressing as division] 21 ÷ 3 = 7 [expressing as division]

12 x 25 = 300 68 x 9 = 612

300 ÷ 25 = 12 [expressing as division] 612 ÷ 9 = 68 [expressing as division]

- Articulating a claim

In natural language expect the students to use phrases like “the factors are being put into a division equation.” Students might indicate what they see in a diagram.

Encourage and scaffold the use of mathematical vocabulary such as factor and product to clarify what numbers are being referred to in the claims. You may need to introduce division terms like divisor (number being divided by), quotient (answer to division) and dividend (the quantity being divided). Encourage clarity by asking questions like:

What does the second factor become in the division equation? (divisor)

What does the first factor become in the division equation? (quotient)

What does the second factor mean?

The aim is to state the claim as something like “Two factors multiply to give a product. The product divided by one factor equals the other factor.”

- Representation

Expect both physical and diagrammatic representations to be used. Be aware that students may interpret division in two ways, as equal sharing (most common) or as measuring. Either interpretation can be used to represent the equations. Here is a measurement interpretation since 48 ÷ 6 is seen as “How many sixes are in 48?”

A sharing view interprets 48 ÷ 6 as “48 is equally shared among six parties. How much does each party get?”

Schematic diagrams, like arrays, show the factors as side lengths, and the product as the area. The missing number in an equation can be shown as an empty measure in the diagram.

- Argumentation

Look for students to justify that if a product, a x b, is the multiplication of two factors a and b, then the product can be divided into sets of b or b sets of a. So the product in multiplication can be thought of as a dividend in division. Either factor can be the divisor, but the other factor is the quotient.

Look for students to accept that the factors and product are variables, meaning they can take up any value. The product is dependent on the factors so can always be represented as a x b, or ab.

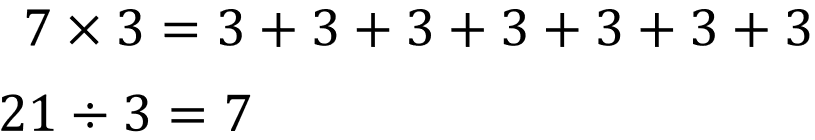

Some students may use the repeated addition view of multiplication like this:

7 x 3 means seven sets of three, so seven sets of three can be made from 21.

a x b means a sets of b, so a sets of b can be made from ab. - Try to scaffold students on from the use of repeated addition by reinforcing more efficient strategies.

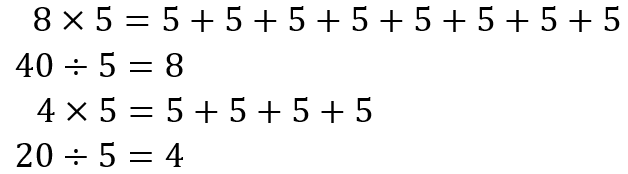

Equation Pairs Set Five

- Noticing regularity

The equation set applies proportional adjustment, halving, of the dividend and explores the effect on the quotient. This property can be used by students to solve division problems. The completed sets should be:

24 ÷ 4 = 6 40 ÷ 5 = 8

12 ÷ 4 = 3 [halving of dividend and quotient] 20 ÷ 5 = 4

264 ÷ 11 = 24 72 ÷ 9 = 8

132 ÷ 11 = 12 144 ÷ 9 = 16

- Articulating a claim

In natural language expect the students to use phrases like “halving the number being divided halves the answer.”

Expect the use of mathematical vocabulary associated with division, like divisor (number being divided by), quotient (answer to division), and dividend (the quantity being divided). Encourage clarity by asking questions like:

What changes in each pair of equations?

What stays the same?

Look at equation four. It is different from the others. How?

The aim is to state the claim as something like “Multiplying or dividing the dividend by a number, while keeping the divisor the same, results in the quotient being multiplied or divided by the same number.”

- Representation

Both equal sharing, or measuring interpretations of division can be used to model the relationships in the equation pairs. Sets models, like stacks of cubes, work well but encourage the progress towards schematic diagrams like arrays.

Note that the fourth equation pair shows the effect of multiplying both dividend and quotient by two.

- Argumentation

Look for students to justify, using words or diagrams rather than symbols. If the divisor stays the same then dividing the dividend by a number results in the quotient being divided by the same number. Similarly, multiplying the dividend by a number results in the quotient also being multiplied by that number.

Look for students to accept that the dividend and divisor are variables, meaning they can take up any value.

Be aware that some students may transfer the repeated addition view of multiplication to division like this:

8 x 5 means eight sets of five, which totals 40. So, with half that total, 20, it is possible to make half as many fives.

If the factors are regarded as variables, then a more general finding might be ‘proven’ geometrically with arrays.

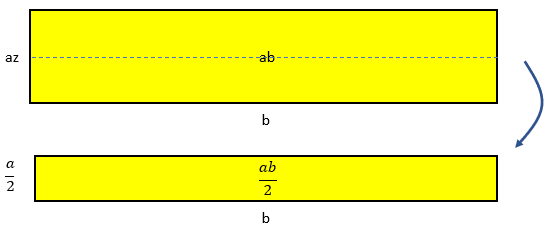

Algebraically this might be expressed as , "If a amounts of b equal ab, then a/2 amounts of b equal half of ab (ab/2)."

Equation Pairs Set Six

- Noticing regularity

The equation set highlights the difference of squares. This property can be used by students to solve multiplication problems. The completed sets should be:

9 x 9 = 81 5 x 5 = 25

8 x 10 = 80 [One less than 81] 4 x 6 = 24 [One less than 25]

20 x 20 = 400 12 x 12 = 144

21 x 19 = 399 [One less than 400] 13 x 11 = 143 [One less than 144]

- Articulating a claim

Expect students to use phrases from their conversational language, such as “The first equation has the same factor times itself. The second equation has one more and one less and the answer is one less.” Ask students to be more specific in their description.

Which factor is increased by one?

Which factor is decreased by one?

Is this true for all four equations?

The aim is to state the claim as something like “If a number is chosen, one less than the number, multiplied by one more than the number, equals the square of the number less one.”

- Representation

Students are likely to use specific examples to convince others about how the relationships work.

- Argumentation

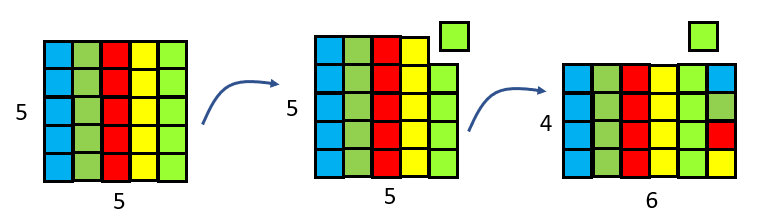

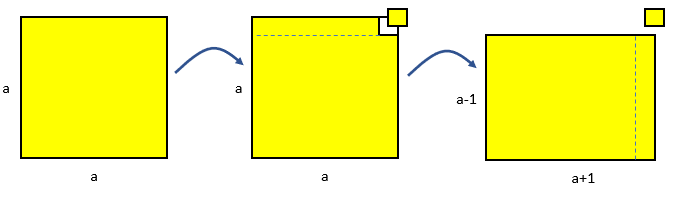

Arrays are a useful representation to ‘prove’ what occurs with the difference of perfect squares.

In general, a2 can be transformed spatially into (a-1)(a+1) by removing one (1 x 1) and moving the unit of (a-1) to create a rectangle with sides of (a-1) and (a+1).

Students are not expected to use algebraic notation at this level. High achieving students might like to see that the transformation can be represented as:

(a-1)(a+1) = a2-a+ a -1 = a2 -1

Equation Pairs Set Seven

Use set seven as an opportunity to see how well students engage in the generalisation process independently. Ask them to record their claims, representations, and arguments in ways that work for them. Some students may prefer writing their work while others may prefer to capture their ideas using a digital recording tool (e.g. Google drawings).

- Noticing regularity

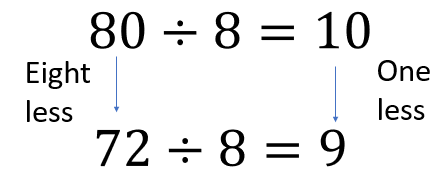

The equation set highlights the division equivalent of the distributive property. The dividend is reduced by a multiple of the divisor. This property is used to solve division problems by rounding the dividend up, e.g. 76 ÷ 4 by calculating 80 ÷ 4 first. The completed sets should be:

80 ÷ 8 = 10 60 ÷ 5 = 12

72 ÷ 8 = 9 [One less set of 8] 55 ÷ 5 = 11 [One less set of 5]

270 ÷ 9 = 30 700 ÷ 7 = 100

261 ÷ 9 = 29 [One less set of 9] 686 ÷ 7 = 98 [Two less sets of 7] - Articulating a claim

Expect students to use phrases from their conversational language, such as “the first equation has a dividend divided by a divisor. The second equation has one or two times the divisor taken off the dividend, so the quotient is one or two less.” Ask students to be more specific in their description. Diagrams might be useful.

Ask questions like:

Show how the dividend is decreased by one or two times the divisor.

What is the effect on the quotient?

Is this true for all four equations?

The claim using mathematical language might be something like, “If the dividend is reduced by one times the divisor, then the quotient is reduced by one.” Note that the fourth equation pair reduces the dividend by two times the divisor.

- Representation

Given the dividends are multiples of ten or 100, place value blocks (MAB) might be a suitable representation.

Schematic diagrams, like arrays, provide a clearer view of the structure found in examples.

- Argumentation

Be aware students might go back to the repeated addition view of multiplication to convince others about their claim. Validate the use of this strategy, and encourage students to develop their use of "noticing regularity". A specific example might look like this:

Dear family and whānau,

This week we have been exploring the properties of multiplication and division. Can your child explain the relationship between multiplication and division?

Ask your child to show you some of the new strategies they have been examining. For example, how to solve;

5 x 26 or 5 x 42

Or how to solve 72 divided by 8 through having the information 80 divided by 8 = 10