This unit geometrically and numerically explores the fact that squaring and square roots are inverses. Gauss’ method of determining square roots when only squares are available is developed. Finally a powerful method of calculating square roots that quickly produces answers to any desired accuracy is shown.

- Calculate square and cube roots.

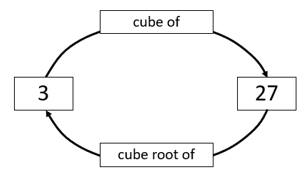

- Understand that squaring is the inverse of square rooting, and cubing is the inverse of cube rooting.

This unit deals with the geometrical measuring and numerical calculation of square and cube roots, and with methods of calculating them without a scientific calculator.

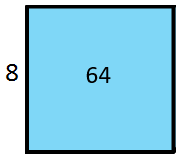

Squaring a whole number gives the area of a square with that length of side. The inverse, finding the square root, gives the side length of a square with given area.

For example, 82 = 8 x 8 = 64 is the area of a square with sides of eight. √64 = 8 gives the side length of a square with area of 64 square units.

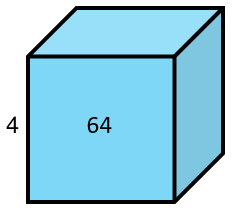

Cubing and finding the cube root are the three dimensional equivalent of this. Cubing a whole number gives the volume of a cube with that length of edge. The inverse, finding the cube root, gives the edge length of a cube with given volume.

For example, 43 = 4 x 4 x 4 = 64 is the volume of a cube with edges of four. ∛64 = 4 gives the edge length of a cube with volume of 64 cubic units.

The learning opportunities in this unit can be differentiated by providing or removing support to students, and by varying the task requirements. Ways to differentiate include:

- beginning with simple squared and cubed numbers and using objects like connecting cubes to model these

- using symbols for squared and cubed numbers alongside physical and diagrammatic models

- asking predictive questions to encourage students to think beyond what is visible

- validating students' use of multiplication strategies, with the aim of moving them towards the use of more efficient strategies

- providing opportunities for students to work in a range of flexible groupings to encourage peer learning, scaffolding, and extension

- modelling and providing explicit teaching around the use calculation of squared and cubed numbers and roots. Gradually releasing your level of responsibility allows you to scaffold students towards working independently

- allowing the use of calculators for making predictions and confirming calculations, and to ease the mental load associated with calculation.

This unit is focussed on exploring squared and cubed numbers, and their roots, and as such is not set in a real world context. You may wish to explore real world applications of squared and cubed numbers at the conclusion of the unit, for example, around dimensions of space (e.g. the area or volume of your classroom).

Te reo Māori kupu such as pūtakerua (square root), pūtaketoru (cube root), tau pūrua and (square number) could be introduced in this unit and used throughout other mathematical learning.

- PowerPoint One

- Copymaster One

- Calculators

- Access to a spreadsheet program (e.g. Microsoft Excel)

- Squared paper

Session 1

- Show the students Slide One of PowerPoint One.

The small crimson square has an area of 1 x 1.

Write some measurements down about the big blue square.

Look for students to identify the side lengths and area.

- Pose the following questions and diagram to students:

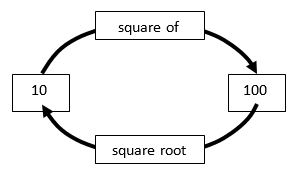

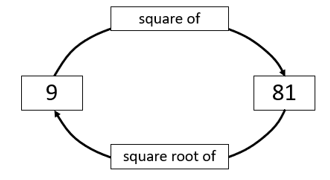

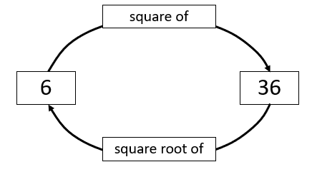

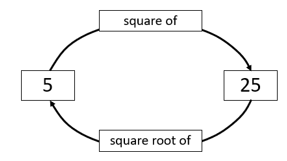

What do you think this diagram represents?

What does squaring give you, if you know the length of one side?

What does finding the square root give you, if you know the area?

- Using the other slides of PowerPoint One, ask your students to create a diagram for each square. For example, for Slide Three write:

- Discuss evaluating √6² using the diagram. Squaring, then finding the square root, is completing a circuit of the diagram (clockwise). The calculation starts on six and ends on six.

- Evaluate (√25)2 using the diagram. This is another full clockwise circuit but starting on 25 and finishing on 25.

- Ask your students if they know of any other pairs of operations that result in a return to the start number. Hopefully students will connect to operations such as doubling (2 x) and halving (÷ 2) or adding n and subtracting n.

- Provide the students with examples of finding areas and side lengths

Possibly extend some students with more complicated examples of finding side lengths. - Slide Five shows a Rubik's Cube which has dimensions of 3 x 3 x 3.

How many small cubes make up this larger cube?

You may want to have a real cube available made from connecting cubes. Ask students how they calculated the answer. Slide Six shows an animation of the cube exploding into three layers of 3 x 3. Model calculating 33 on the calculator. - Explain:

Squaring gives the area of a square from the side length.

Cubing gives the volume of a cube from the edge length.

What do you think might give the edge length from the volume?

- Use the Rubik's Cube to introduce this diagram:

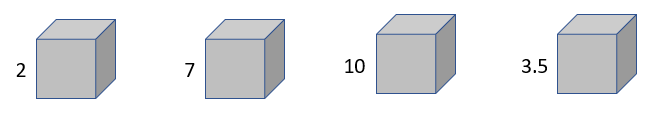

Slides Six, Seven, Eight and Nine give other examples. Ask students to create diagrams for those graphics. Have real models available if needed.

- Provide students with time to complete the following tasks: (see Copymaster One for independent examples).

Find the volume of these cubes.

Find the edge lengths of these cubes.

Encourage students to use the flow diagram, perhaps modelling and helping them to construct this, as needed.

Session 2

- Tell students: Carl Fredrick Gauss was a mathematical genius who found a way to add all the numbers to 100 when he was just nine years of age. He also created a method of computing square roots, using iterative (repeated) approximation. You could ask students to research Gauss, and then collate and share your research as a class.

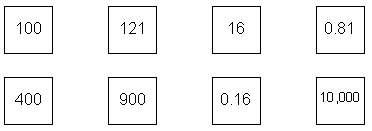

Present students with a table of squares like the one below.

Ask: How might we use the table to estimate the square root of 38?Number

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Number

1

4

9

16

25

36

49

64

81

100

- Discuss how this table shows that √38 lies between 6 and 7 since 62 = 36 and 72 = 49. You could write 6 < √38 < 7 and discuss the meaning of the less than and greater than symbols.

What number is half way between 6 and 7?

Let’s see whether squaring 6.5 gets us closer to 38.

- Allowing only the use of the squaring button work out 6.52 = 42.25

- Discuss how this shows 6 < √38 < 6.5 because 42.25 is greater than 38.

Try 6.3 and 6.2 because they are about half way between 6 and 6.5.

6.32 = 39.69 and 6.22 = 38.44. What does this tell us about √38?

- Discuss why 6 < √38 < 6.2.

Try 6.12 = 37.21

What does this tell us about √38? (√38 is between 6.1 and 6.2)

That might be close enough but what if you wanted more accuracy? What could you do?

Students might suggest that you could try 6.15 to see if √38 is less than or greater than 6.15. Since 6.152 = 37.8225 that shows 6.15 < √38 < 6.2. The method can be used repeatedly until a required number of decimal places is reached.

- Try 6.182 = 38.1924

- Discuss why 6.15 < √38 < 6.18 and show why 6.16 < √38 < 6.17.

- Provide time for students to do the following:

- Locate the following square roots, using Gauss' method, to within 0.1 of the answer.

√53

√91

√41

√77

√81.4

√10.6

- For extension, repeat 2 of the above, locating the square roots to within 0.01 of the answer.

- Graph the squares of numbers from zero to one.

- Create this table and graph the ordered pairs.

x 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1 y=x2 0 0.01 0.04 0.09 0.16 0.25 0.36 0.49 0.64 0.81 1

- As a class, siscuss how to obtain square roots from the graph. Discuss how to graph the data to increase the accuracy adding extra points and expanding the x and y scales.)

- Finish the session with this problem (or one similar, with an adapted context):

Hine has 24 metres of chicken wire to make the boundary of her chicken run.

She wants the run to be a rectangular shape.

What length should she make the sides?

Session 3

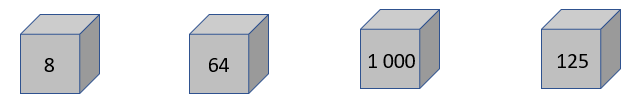

Extend the Gaussian algorithm to finding cube roots to a desired accuracy. Discuss how this table helps show that 4 < 3√110 < 5:

Number

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Number3

1

8

27

64

125

216

343

512

729

1000

- Discuss why 3√110 must be nearer to 5 than 4 (because 110 is closer to 125 than 64).

What number could we try next to get closer to the cube root?

Students might suggest 4.7 or 4.8.

How do we check those numbers? (cube them – multiply each by itself then itself)

4.73 = 103.823 and 4.83 = 110.592

So 4.7 < 3√110 < 4.8 a

Is 3√110 closer to 4.7 or 4.8? How do you know?

- Let the students continue the process to find 3√110 to two decimal places.

- Provide time for students to find these cube roots to one decimal place:

- 3√37

- 3√79

- 3√218

- 3√984

- 3√462

- 3√5

- Discuss:

If 23 = 8 what does 24 mean?

If 3√64 = 4 what does 4√81 mean?

It is not possible to show a physical representation of raising a number to the power of four and finding the fourth root. Discuss the fact that mathematicians often create ideas in their heads before a practical application is found for those ideas.

- Pose this problem:

Is 2.59 < 4√45< 2.6 correct?

2.594 = 44.99860561 and 2.64 = 45.6976

So the statement is correct.

- Provide time for students to determine which of the following statements are correct:

- 4√625 = 5

- 2.64 < 4√625 < 2.65

- 74 = 492

- 5.364 < 5√4444 < 5.365

- 4√0.0016 = 0.2

- 3√5.0625 = 4√11.390625

Session 4

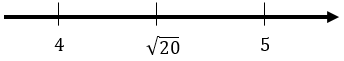

- Explain to students: Jessie is calculating √20. She guesses 5, knowing that 5 is too big.

How does she know that?

Next, she divides 20 by 5 and gets 4. She knows that 4 is too small.

How does she know that?

Jessie thinks that the average of 4 and 5, ½(4 + 5) (four plus five, divided by two), will be closer to √20 than either 4 or 5.

How does she know that the average must be closer?

Averaging gives ½(4 + 5) = 4.5 which is better than either 4 or 5.

Jessie repeats the process using 4.5. She calculates 20 ÷ 4.5 = 4.4 (four point four recurring).

What does she know from that calculation?

Finding the average of 4.5 and 4.4 will give her an even closer estimate of ½(4.5 + 4.4) = 4.472 (four point four seven two recurring).

Teacher note: √20 = 2√5. Therefore, the decimal will be non-terminating.

What could Jessie do now if she wants even more accuracy?

Repeating the process using 4.472 gives the following average:

½(4.472 + 4.472049…) = 4.4721359…

Check this number against the actual √20 = 4.4721359…

- Discuss why this method of finding square roots is superior to Gauss' method. (accurate results are obtained much more rapidly). The method is usually attributed to the ancient Babylonians or to Hero, a Greek mathematician. The method is well over 2000 years old!

- Provide time for students to find the following, correct to 3 decimal places.

- √188

- √69

- √14

- √4.06

- √0.25

- √713

- √0.0811

- √66,000,000

- √0.643

- √7,777

- √2

- Challenge students to create a spreadsheet to find square roots rapidly using the Babylonian method. Remember that the spreadsheet needs to be user friendly.

Teacher note: The exercise develops computational thinking in that students develop an iterative (repeating) algorithm.

- Example: This spreadsheet shows how this can be made. Calculating the square root of 345 using 18 as an initial approximation is modelled. If you provide this spreadsheet to your students, ensure that they look at the formulae in the cells and discuss what they do. Discuss the purpose of the $ signs in column C.

- Provide time for students to use their spreadsheet to find:

- √555

- √5555

- √1888

- √600,413.8

- √0.0689

- √0.966631

- √400,786,000

- √123,456.789

Dear families and whānau,

We have been exploring different method for calculating square roots. Ask your child to share their learning with you.