This is a level 4 link measurement activity from the Figure It Out series. It relates to Stage 6 of the Number Framework.

Click on the image to enlarge it. Click again to close. Download PDF (148 KB)

solve problems involving 24 hour time and time zones

classmate

FIO, Geometry and Measurement Link, Sorry to Disturb you! page 24

phone book

This activity gives students opportunities to explore the effects of crossing the International Date Line and to work out what time it is in different countries and time zones, using the information in the phone directory.

Activity

The International Date Line is an imaginary north–south line on the surface of the Earth that allows us to define the time of day with precision and separates “today” and “tomorrow”. Many students do not realise that 24-hour time is a human construct and that the lines of longitude that enable us to assign a time to any

place on the planet were set in place in recent history in response to navigational needs. A very interesting mathematical and historical investigation could be based around this topic.

The International Date Line follows the 180° meridian (on the opposite side of the Earth to the 0° meridian, which goes through the Greenwich Observatory in London), zigzagging around eastern Russia and making a major detour in the Pacific Ocean to ensure that all the islands of Kiribati are on the same side.

You could introduce this activity by using a torch to represent the Sun (and daytime) and a globe that shows the International Date Line. Show the students how the Sun shines on different parts of the world as the Earth spins on its axis. Try these questions as discussion starters:

- What countries are on the opposite side of the Earth from New Zealand?

- What time would you expect it to be there when it’s lunchtime here?

- Which way does the Earth spin on its axis, given that the Sun rises in the east and sets in the west?

- Where on the surface of the globe should you look for sunrise and sunset?

When introducing question 1, ask your students if they have ever lost or gained time when travelling overseas. Get them to talk about their experience of moving forwards or backwards through time zones and how this often affects sleep.

Using a globe or a soccer ball and a paper dart or a toy aeroplane, ask the students to try to explain how Courtney missed her birthday. Ask them to try to explain how, if she timed it correctly, she could use international travel to have 2 birthdays in 1 year. (She could manage this if she left on the day of her birthday and crossed the International Date Line from west to east, gaining 24 hours.) Ask “Would this mean that she went from age 11 to age 13 in 24 hours?”

When doing questions 2 and 3, students may find it helps them to visualise what is going on if they have an analogue clock that they can turn backwards. If they do use a clock, they will need to keep track of whether it is morning or evening and what day it is if they move back past midnight. Explain that a.m. is the abbreviation for ante meridiem (Latin for “before noon”) and p.m. is the abbreviation for post meridiem (Latin for “after noon”).

Students who know the part–whole strategy “building to a tidy number” can be encouraged to apply the strategy to this problem, using 12 noon and 12 midnight as tidy numbers. 18 hours before 9 a.m. on Wednesday can then be solved in this way: “If we subtract 9 hours from 9 a.m., we get back to 12 midnight on Tuesday; if we then subtract 9 more hours (to make the total of 18 hours), we get back to 3 p.m. on

Tuesday.” Using a number line, we can illustrate these two steps like this:

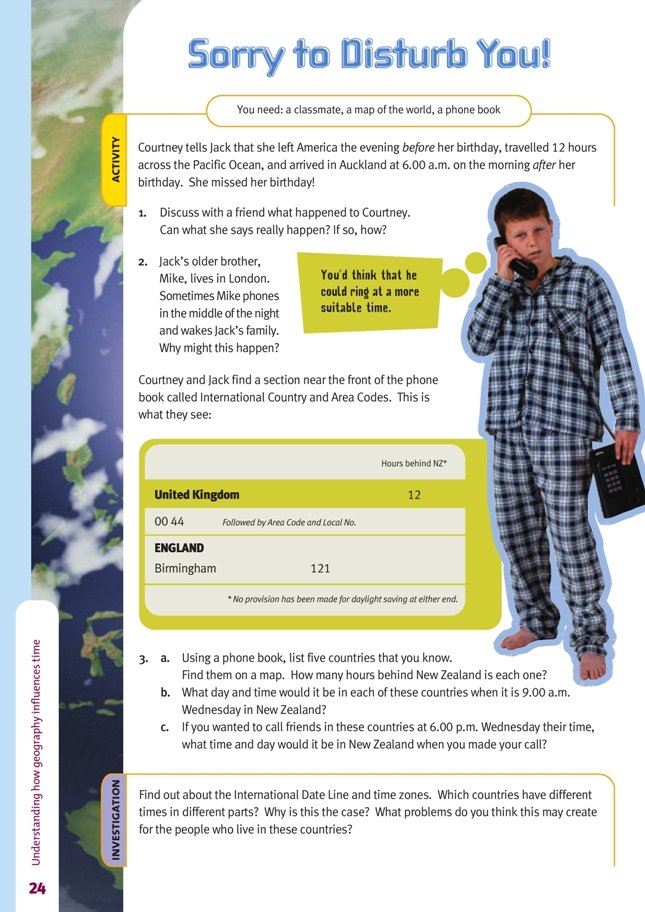

The note in the phone book “No provision has been made for daylight saving at either end” is a reminder that the times in the phone book are based on Greenwich Mean Time and that many countries put their clocks forward by an hour during the summer months. (GMT is still widely used, though technically superseded by atomic time.) This is to take advantage of the extra daylight in summer that comes as a result of the tilt in the Earth’s axis, which brings us closer to the Sun.

If we know that a country has daylight saving or “summer time” at the moment, they will be 1 hour less behind us than the number stated in the phone directory because they will have put their clocks forward. When it is summer in the United Kingdom, they are 11 hours behind us instead of 12. However, when New Zealand is on daylight saving time, we are forward by an extra hour, meaning that in our summer months, we are actually 13 hours ahead of the United Kingdom. There are only a few weeks of the year when neither the United Kingdom nor New Zealand is on daylight saving time and when, as a consequence, we are exactly 12 hours apart. Some students may wish to do some research into daylight saving or Greenwich Mean Time.

If students want to make sure their calculations take account of daylight saving times, there are a number of websites that have this information, including www.whitepages.co.nz/world-directories

At the conclusion of this activity, use these suggestions to encourage your students to reflect on what they have learned:

- Why doesn’t New Zealand need to have different time zones within our country? (Because we are long and thin and orientated north–south, so the Sun rises and sets at a similar time throughout the country. By contrast, in Australia there is a big distance between the east and west coasts of the continent, so they have 2 hours’ difference between Sydney in the east and Perth in the west.)

- Share something interesting or new to you that you found out from this activity or from your research.

Answers to Activity

1. The sort of thing Courtney describes happens every time a person crosses the International Date Line. If they cross from west to east, they gain 24 hours;

if they cross from east to west, they lose 24 hours. Courtney left the evening before her birthday and travelled for 12 hours, so she should have arrived on the morning of her birthday, but because she crossed the Date Line on the way, it wasn’t her

birthday, but the day after it.

2. This is a common problem. London is 12 hours behind New Zealand, so when it is 10 a.m.–7 p.m. there (good times for phoning), it is 10 p.m.– 7 a.m. in New Zealand (good times for sleeping). 8–10 a.m. in London is 8–10 p.m. here (and vice

versa), which is a time slot likely to be suitable for a phone conversation at either end.

3. a. Practical activity

b. Practical activity. Don’t forget to note the day as well as the time. (Example: ringing Vancouver in Canada, which is 20 hours behind New Zealand. Take off 24 hours, which makes the time 9.00 a.m. on Tuesday. Add 4 hours back on to this, which makes the time in Vancouver 9.00 + 4.00 = 1.00 p.m. on Tuesday.)

c. Practical activity. (Example: ringing Sàmoa, which is 23 hours behind New Zealand. Add 24 hours to the time in Sàmoa, which gives a time of 6.00 p.m. here on Thursday. Take 1 hour off this, which means that 6.00 p.m. Wednesday in Sàmoa is 5.00 p.m. Thursday in New Zealand.)

Investigation

Answers will vary.