This unit supports students in developing procedural fluency with the multiplication and division of integers, and in developing conceptual understanding of how integers are used in the real world.

- Understand everyday applications of integers.

- Multiply and divide positive and negative integers.

- Use models to explain why the multiplication of integers has a positive or negative effect.

Integers are an extension of the whole number system. Therefore, the properties of integers under the four operations should be the same as those for whole numbers. This is described below. Note that the four main properties hold for multiplication but not for division. Furthermore, the set of integers is not closed under division.

The commutative property of multiplication

The order of the addends does not affect the sum. If -3 x 4 = -12, then 4 x -3 = -12. Note that the commutative property does not hold for division. For example, 12 ÷ -3 = -4 but -3 ÷ 12 = -¼.

The distributive property of multiplication

This property, pertaining to the partitioning of factors and recombining those factors, states that a x (b+c) = (a x b) + (a x c). For example, if 5 = -1 + 6, then -3 x 5 = -3 x (-1 + 6) = -3 x -1 + -3 x 6. This property does not hold for division.

The associative property of addition

This property, pertaining to the ‘associating’ of pairs of factors, one pair at a time, states that the grouping of the numbers does not affect the answer. For example, (-4 x 3) x -1 = -4 x (3 x -1). This property does not hold for division.

Inverse operations

Multiplication and division are inverse operations so one operation undoes the other. For example, -2 x -3 = -6 so -6 ÷ -3 = -2.

It is the need for these number laws to hold, that establishes the effect of operations. For example, the multiplying of two negative integers has the same effect as the multiplying of two positive integers.

Lack of closure

The set of integers is not closed under the operation of division. This means that the quotient (answer) for division of an integer by another integer is not always another integer. This lack of closure gives rise to the need for the set of rational numbers.

Specific Teaching Points

Many representations of multiplication and division of integers are problematic on two grounds:

- Physical modelling of multiplication and division of integers in practical ways is often contrived, especially operating with negative multipliers and divisors;

- Models are often applications of the operations so are not suitable to introduce those operations, for example transmission factors for gears and pulleys

- Physical representations are sometimes more complex to interpret than the concept they illustrate.

Hans Freudenthal (1983) introduced two models for operations on integers, the annihilation and vector models. In the annihilation model positive and negatives cancel each other, so +1 and -1 pairs equal zero. The act of creating or removing one positive and one negative integer from a pair to equal zero does not alter the quantity being represented. The vector model presents integers as magnitudes with direction. +1 is represented by a vector of length one in a positive direction and -1 as a vector of length one in a negative direction. Both the annihilation and vector models transfer to multiplication and division of integers as repeated addition and subtraction, but will need to be broken down practically in some examples. In 1993 Marcia Cooke introduced a videotape model to represent the multiplication of integers. The factors in the situation were directional speed, in a positive or negative direction, and time, either forward or backward. Cooke’s model adapts to division though creation of ‘missing factor’ problems.

Freudenthal suggested that prompt application of the integer operations was essential for students to appreciate the new possibilities created by enlargement of the number system. In particular, he favoured work with functions in both algebraic and graphical form.

The learning opportunities in this unit can be differentiated by providing or removing support to students and by varying the task requirements. Ways to support students include:

- appropriately modelling operations using positive and negative integers

- using physical and diagrammatic models in conjunction with symbols so students can work out the answers to calculation by linking the symbols to quantities, e.g. cash as positives and debts as negatives

- modelling correct equations for calculations. Be clear about the difference between an operation symbol, and a direction symbol such as -4 which gives a direction of movement and the size of that movement

- using calculators in a predictive way - that is thinking about the answer using models, then testing out the answer on a calculator. Further to this, have students use calculators to generate patterns of equations quickly, and expect students to generalise from the patterns. For example, subtracting a negative has the same effect as adding the matching positive

- encouraging sharing and discussion of students' thinking

- using collaborative grouping so students can support each other and experience both tuakana and teina roles, and mahi tahi (collaboration)

- extending more knowledgeable students by providing opportunities for them to create problems as a resource for their peers, and as a way to consolidate and demonstrate their own understanding

- creating a shared class chart of key terms and concepts at the conclusion of each session. This can be revisited at the start of each session as a way to review learning.

The unit frames learning in a wider variety of contexts, including money, hills, time, speed, length, area, gears, and pulleys. Consider how you might adapt or replace these contexts with ones that better reflect the interests and cultural backgrounds of your students, and that might make interesting links with learning from other curriculum areas. Students interested in sports might enjoy golf as a context, and those who enjoy computers might find points schemes interesting. Some students may enjoy the context of comparing temperatures from locations around the world. Investigating local places that are above and below sea level could also be an engaging context for students.

Te reo Māori vocabulary terms such as tau tōpū (integer), tau tōraro (negative number), and tau tōrunga (positive number) could be introduced in this unit and used throughout other mathematical learning.

- Copymaster One

- Copymaster Two

- Copymaster Three

- Copymaster Four

- Copies of Figure It Out activity Sign of the Times (optional)

- Animation Two A

- Animation Two B

- Animation Two C

- Animation Two D

- Animation Two E

- Animation Two F

- Animation Two G

- Animation Three A

- Animation Three B

- Animation Three C

- Animation Four A

- The Biscuit Factory learning object (optional)

- Access to Geogebra (freely available online)

- Access to e-ako (Multiplicative thinking pathway: R4.40: Gears as a context for ratios and R5.10: More gears as a context for ratios)

Prior Experience

It is important that students have prior experience with addition and subtraction of integers prior to being introduced to this concepts in this unit. Since multiplication is founded on repeated addition, and division on repeated subtraction, knowledge of these operations is essential. Students need to distinguish between integers as quantities (magnitudes with direction) and operations as actions performed on those quantities. For that reason, try to avoid over-simplifications such as ‘two negatives make a positive’, since the negative signs involved relate to different things (direction and operation).

Session One

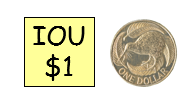

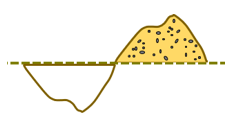

This session introduces multiplication of integers using the annihilation and vector models used in the Level 4 unit Integers. The model represents +1 as a black arrow to the right and -1 as a red arrow to the left (see Copymaster One). Beginning at zero, and combining +1 and -1 in any order, results in a destination of zero. Contexts that can be linked to the addition of +1 and -1 include:

One hill fills one dale One dollar pays one IOU

- Pose this problem to the students:

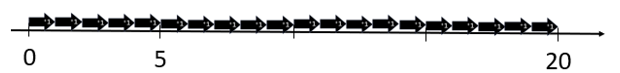

Jen gets $5 spending money per day from her parents. How much money does she get from them in four days?

Look for students to recognise this as a simple equal sets multiplication scenario that can be expressed as 4 x 5 = 20. By changing the unknown, two division problems can be created:

- Jen gets $5 spending money per day from her parents. They give her $20. How many days of spending money is that? (20 ÷ 5 = 4)

- Jen gets the same amount of spending money per day from her parents. They give her $20. That is four days allowance. How much do they give her per day? (20 ÷ 4 = 5)

You might model the problems using arrows from Copymaster One or with chalk drawings on concrete.

- Extend the scenarios using either the money or hills metaphors to include problems where a positive integer is the multiplier and integers of either sign are the multiplicand. For example:

- Ceilia, the roading engineer has four sections to seal. Each section has five dales. How many dales in total will need to be filled? [4 x -5 = -20]

- Ceilia, the roading engineer has four sections to seal. Each section has the same number of dales. She reports that her earth situation is -20. [-20 ÷ 4 = -5]. How many dales are in each section?

- Record some multiplication equations in pairs, such as:

3 x 8 = _ and 3 x -8 = _ 6 x 7 = _ and 6 x -7 = _ 9 x 2 = _ and 6 x -2 = _

- In each case, ask the students how the equations might be modelled with arrows, hills and dales or money and IOUs. Ask:

What the product would be? Why?

Are there some multiplication types we don’t know the answer to?

Students may say that when the first factor is negative the model does not make sense. It is not physically possible to have negative sets of anything.

- Ask: What would -3 x 8 = _ mean? Could we make that problem? What about -3 x -8 = _?

- Ask students what they think the answers could be. Some might mention the commutative property, e.g. If 8 x -3 = -24 then -3 x 8 = -24. Others might attend to the signs, e.g. If there is one negative sign the answer would be negative so if there are two negative signs the answer should be positive. This response is informal use of the associative property, e.g. -3 x -8 = (-1 x 3) x (-1 x 8) = (-1 x -1) x (3 x 8).

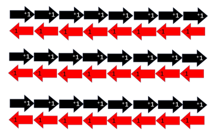

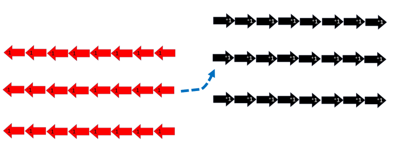

Some might mention that a positive multiplier means that sets are repeatedly added so a negative multiplier must mean the opposite, that sets are repeatedly subtracted. Therefore -3 x 8 = _ means the removal of three sets of eight which results in a ‘deficit’ of -24. The annihilation model of this interpretation relies on making 24 zeros then removing three sets of eight.

Make 24 ‘zeros’

Take away three sets of eight leaving -24.

- Let students test out their theories of what occurs with negative multipliers by working through Copymaster One and Copymaster Two. Alternatively, have them work on the Figure It Out activity Sign of the Times. This could be used as an early finishers task, and could provide you with the chance to work with small groups and individuals in needed of more support.

Session Two

In this session students explore Marcia Cooke’s model for multiplication of integers.

- Start by showing the students Animation Two A. Ask them what the animation shows. The kiwi walks for three hours at two kilometres per hour and covers a total distance of 6 kilometres. Ask students how this animation might be represented by an equation [3 x 2 = 6].

What do the 3, 2 and 6 refer to?

- Watch Animation Two B. This shows kiwi walking in a negative direction (backwards) for three hours at a speed of two kilometres per hour. How might this animation be represented as an equation? [3 x -2 = -6] What do the numbers 3, -2 and -6 refer to?

- Ask the students what they think both animations would look like if they were played backwards. How would kiwi’s movement in each case be represented by an equation? Let the students discuss their predictions before gathering the class together.

- Refer to the meaning of the numbers in each equation. For Animation Two A we wrote 3 x 2 = 6. What changes when we play the animation backwards? [3 x -2 = -6, both speed and distance change in an opposite direction]. Create a table to organise the predictions.

| Negative Speed | Positive speed |

Negative Time | -2 x -3 = __ | -2 x 3 = __ |

Positive Time | 2 x -3 = -6 | 2 x 3 = 6 |

- Play Animation Two C which shows time going backwards for three hours while kiwi is travelling at two kilometres per hour in a positive direction. The effect of this is that kiwi moves backwards a distance of 6 kilometres. If kiwi started at zero, its destination would be -6 kilometres. Therefore -2 x 3 = -6.

- Play Animation Two D which shows negative speed multiplied by negative time. Kiwi goes back in time by three hours at a speed of negative two kilometres per hour. The effect is that it moves 6 kilometres in a positive direction. If the video started with kiwi on zero it would end up on positive six kilometres. Therefore -2 x -3 = 6. Play Animation Two E to confirm this effect.

- Play two more animations, Animation Two F and Animation Two G. For both clips ask how kiwi’s journey could be written as an equation, what would occur if time was run backwards, and the associated equation with time being negative.

- Animation Two F shows 3 x 3 = 9 so backwards the clip would show -3 x 3 = -9.

- Animation Two G shows 4 x -3 = -12 so backwards the clip would show -4 x -3 = 12.

- Ask your students to work through Copymaster Three in small groups or individually. The problems require the students to apply their understanding of multiplication. Roam and provide support. You might provide students with access to the animations (e.g. on a PowerPoint) for them to refer back to. After a suitable time gather the class to discuss their answers. Model the solutions to the problems, review key knowledge, and address any misconceptions as they arise in discussion.

Problems One and Two

- Do the students recognise that distance is the multiplication of speed by time?

- Do they accept that time and speed can be negative or positive?

With Problem One:

- Do students generalise that each pair of factors has a positive and negative possibility? For example, 4 hours at 60 kph [4 x 60 = 240] has a negative possibility [-4 x -60 = 240] which is the scenario of the camper van travelling at a speed of -60 kph backward in time for -4 hours.

With Problem Two:

- Do students generalise that each pair of factors generates two possible answers by swapping of signs? For example, 5 minutes at -120 metres per minute [5 x -120 = -600] is the same effect as -5 minutes at 120 mpm [-5 x 120 = -600].

Problem Three

- Expansion of the number system to include integers results in 36 having two square roots, 6 and -6.

- Do the students provide many example and justify why this is true?

Session Three

In this session students apply the multiplication of integers to enlargement (dilation) of figures. Students will need access to Geogebra which is a free download. The videos listed below were created using Geogebra and we appreciate their support in allowing us to provide them copyright free.

- Play Animation Three A. It shows how to dilate (enlarge) a figure by scale factor of positive three. Before students try creating the transformation themselves ask what changes and what stays the same as the figure is enlarged. They should note the following:

| Unchanged | Changed |

Angles Order (Way parts of figure are connected) Orientation (Direction the figure is facing) Ratios of side lengths | Lengths (x 3) Area (x 9) |

Changes in length and area can be checked using key points. The algebra window gives the co-ordinates of points from the figure and the corresponding points in the image.

- Let the students create their own enlargement. Encourage them to experiment using scale factors between zero and six, and enlargement factors that are fractions. You might model the use of Geogebra before, and as, students complete the task.

- Confirm that the enlargement factor specifies the scalar for length. Areas are scaled by the square of the scale factor. Students need to also realise that the term enlargement is misleading. A scale factor of 0.5 changes lengths to one half of the original figure so the size of the image is smaller than the original figure.

Animation Three B shows what happens when a figure is enlarged by a factor of -3. Look again at the variant and invariant features. The change to orientation is particularly interesting. The image is upside down and facing the other way compared to the original.

- Direct students to follow the instructions on Animation Three B to experiment with enlargements by negative factors, and to try an enlargement factor that is a negative rational number, like -3/2.

- Animation Three C shows how to create sliders to control combinations of enlargements. Ask the students to create their own sliders then pose the following problems:

- When you combine enlargements how do lengths change between the original and the second image?

- When you combine enlargements how does orientation change between the original and the second image?

- How is the combination of enlargements related to multiplication of integers?

- Let the students explore to find answers to these questions. Do they…

- Notice that change to length is by the product of the two scale factors, e.g. Scale factors of 2 and 3 produce an image with lengths 3 x 2 = 6 times as long as the original.

- Notice that the number of negative signs in the scale factors determine the orientation of the second image, e.g. Scale factors of 2 and -3 produce an image with opposite orientation.

- Represent these two results using multiplication, e.g. -2 x -3 = 6 represents scaling a figure by -3 then -2 which results in an image of length six times larger than the original and orientated in the same way as the original.

Students might like to explore what happens with three of four combined enlargements. It is interesting to explore combinations of scale factor -1.

Figure It Out, Number Book Six, Level 4+, page 24 shows how negative enlargement is used in photography and explores the proportional nature of enlargement.

Session Four

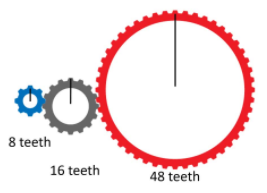

In this session the students explore another application of multiplication of integers, gears and pulleys.

- Begin with a reminder about application to enlargement. Address the following key points:

- When a figure was enlarged by a negative scale factor what happened?

- Lengths increased by the scale factor and orientation changed.

- What happened when two negative enlargements were combined?

- The image finished in the same orientation as the original and its lengths were the product of the scale factors.

Comment that students are going to see another situation where a rate and direction can be represented using integers.

- Show the students Animation Four A but do not start it. Ask where in real life gears are likely to be found, e.g. bicycles, cars, conveyor belts, watches (clocks), large doors or gates.

If the blue gear is attached to a motor and drives the red gear. What will happen to the red gear in each picture as the blue gear turns once? In both situations the red gear will turn twice which is a transmission factor of two. But in the pulley gear (left) the turn will be in the same direction as the drive gear and in the direct gear (right) the turn will be in the opposite direction. The transmission factors are 2 and -2 respectively. How is this like the enlargement situation?

Animation Four A continues and shows the turning of gears. It provides other examples. Stop at each new gear setup and ask the students to name the transmission factors.

You may like to use The Biscuit Factory learning object with your students . This learning object explores gear ratios though it neglects the integer connection. It is a Flash object so is not supported on some devices.

The rest of the lesson is devoted to students working from two e-ako from the Multiplicative thinking pathway (R4.40: Gears as a context for ratios and R5.10: More gears as a context for ratios) These e-ako activities constitute a sequence which culminates in students understanding how the transmission factors in a gear train can be multiplied to find the combined transmission factor. This makes connections to proportional reasoning and the multiplication of fractions. For example, in the train below the blue gear drives the grey gear which in turn drives the red gear.

The grey gear turns 180◦ for each 360◦ turn on the blue gear, in an opposite direction. The transmission factor is -½. The red gear turns 120◦ for each 360◦ turn of the grey gear, in an opposite direction, so the transmission factor is -⅓. The combined effect is the result of -½ x -⅓ = -¹/₆. The red gear makes a 60◦ turn in the same direction for each 360◦ turn of the blue gear.

Session Five

In this session multiplication and division of integers is generalised, allowing students to investigate number patterns with the operations. Although students do not need to formally refer to the commutative, associative and distributive properties, those properties are implicit in the number patterns they will explore.

- Ask: What two numbers can be multiplied to get an answer of 14? (not negative 14). Hopefully students will suggest 2 x 7 or 7 x 2 and -2 x -7 or -7 x -2. Record the answers using a two-way table like this.

x | 2 | -2 |

7 | 14 | |

-7 | 14 |

- Ask: What answers are missing from the table? Students should tell you that 2 x -7 and -2 x 7 give answers of -14. From the one example, generate this two-way table.

x | + | - |

+ | + | - |

- | - | + |

- Tell the students to work in pairs on Copymaster Four. Allow them to use their calculators but only to check their predictions.

- After a suitable period, discuss how the rules for multiplying and dividing integers might be recorded. Let students offer suggestions about how best to record the generalisations. You might discuss ways to write the rules algebraically.

Suppose we call the integers we multiply a and b. We write {a, b} ε I. What does that mean?

How do we say that a and b are both positive (a, b > 0)? ..both negative (a, b < 0)?... one negative and one positive (a>0 and b<0 or b>0 and a<0)?

If a and b are the Integers we multiply together how might we say the product is positive? (ab>0 )… negative? (ab<0) …equal to zero? (ab = 0).

What do we know about a and b if the product equals zero?

Can we write similar rules for division? Is the answer always an integer?

What about division by zero? What happens then? How do we write that anomaly as a rule?

- Provide time for your students to create problems involving the multlication and division of integers for their peers. Emphasise that these problems should be situated in a relevant context - you might choose this, or generate a list of possible contexts with your students.

Dear families and whānau,

This week we are learning about multiplying and dividing positive and negative numbers. The rules are a bit tricky but we will be working on understanding why things happen and looking at real world applications. Does anyone use integers? It turns out they do!

For example, when we multiply two negative numbers together the product is positive. Why does that happen? Perhaps your student can explain.