This unit explores the volume (in cubic units) of skyscraper constructions. Students investigate the most efficient way to pack cuboids in a confined space, and the relationship between millilitres and cubic centimetres

- Use a formula to calculate the volume of cuboids by measuring the length of each of the three dimensions.

- Investigate the relationship between millilitres and cubic centimetres.

This unit leads to an application of the formula for the volume of cuboids, namely that the volume is found by multiplying the length by the height by the depth.

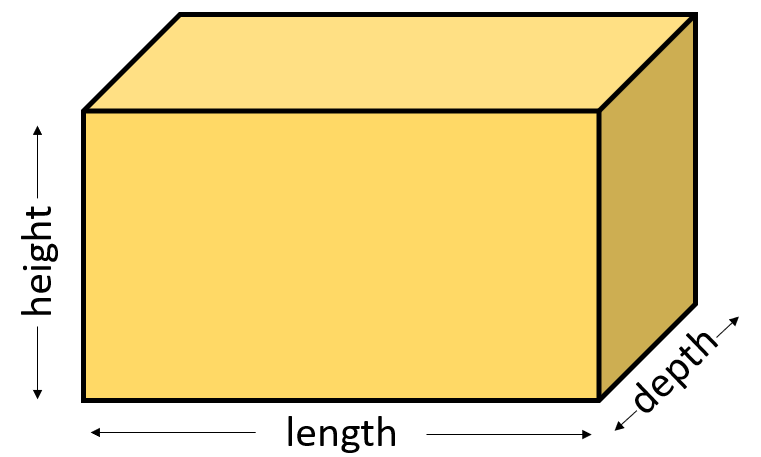

Volume of a cuboid (rectangular prism) is given by V=l×h×d. In general, calculating the volume of three-dimensional shapes requires measurements of those three dimensions.

In the application, different volumes are calculated by combining cuboids to make a variety of shapes. This reflects a common approach to finding volume (or area) by breaking up complicated shapes into simpler ones, for which the volume (or area) is easier to find.

The unit also leads to the discovery of the fact that 1000 cubic centimetres (1000 cm3) occupy the same space as one litre of water. One cubic centimetre (1 cm3) and 1 millilitre (1 mL) represent the same amount of space. In the metric system, the cubic centimetre is a unit of volume, that amount of three-dimensional space bounded by an object. The millilitre is a unit of capacity, the amount of liquid or gas that is contained in an object. The designers of the metric system connected the units for volume, capacity and mass using water. One millilitre (1 mL) of water has a volume of one cubic centimetre (1 cm3), and a mass of one gram (1 g).

The learning opportunities in this unit can be differentiated by providing or removing support to students, or by varying the task requirements. Ways to support students include:

- altering the numbers that you choose for the problem. Choose packets where the edges are whole numbers of centimetres before progressing to fraction lengths. Constrain the size of the packets so it is easier to completely fill them.

- working with students’ preferences for additive thinking to develop their multiplicative thinking. For example, show how the volume of a single layer of cubes can be calculated by multiplication, then build up stacks of that layer. Explicitly show students how multiplication of two edge lengths gives the volume of one layer, and multiplication by three edge lengths give the total of all the layers.

- allowing students to experiment with constructing different cuboids so they learn that physical appearance can be misleading. Tall cuboids do not always have greater volume than shorter cuboids. Comparing the volume of cuboids helps students to realise that all three dimensions contribute to volume.

- using calculators to ease the demands especially where finding factors is required, e.g. Make a cuboid packet with a volume of 400cm3.

- encouraging sharing and discussion of students' thinking

- using collaborative grouping so students can support each other and experience both tuakana and teina roles

- encouraging mahi tahi (collaboration) among students.

The contexts used in the unit can also be adapted to cater for the cultural backgrounds and interests of students. Choose situations that are likely to be familiar to your students. The use of everyday packets and skyscrapers is likely to be motivating to many students. Packing cuboids might be more relevant in the context of packing the boot of a car for a week away or packing a suitcase. Filling a box with Christmas gifts for whānau in another destination, like Samoa, might appeal to some students. The volume of baskets (kete) could also be connected to learning about the traditional story Tāne ascends to the heavens, and learning about the varied purposes of kete (e.g. for storing food, as everyday bags, as a symbol of knowledge and resilience). Volume is also used to represent the size of appliances, like refrigerators and dishwashers. In a technology context, learning around volume could be applied to creating new containers for a product.

- 30 cm rulers

- Connecting cubes (a large supply)

- Place value blocks (including one large cube)

- Scissors, and tape

- Calculators

- Small cardboard packets such as toothpaste, milo, muesli bar, crackers, brought from homes

- One litre milk carton

- Copymaster 1

- Copymaster 2

- Copymaster 3

- Copymaster 4

- PowerPoint 1

- PowerPoint 2

- PowerPoint 3

Session One

- Arrange five cardboard packets of similar volume but different appearance on a desktop.

What is the same about the shape of all these packets?

Students will spot many commonalities that are all valid, e.g. made of cardboard, shaped like rectangles, six faces, etc. Focus the students’ attention on the shape features the boxes have in common. All five boxes are composed of six rectangles.

Is there a mathematical name for boxes of this shape?

Students may know that all the boxes are rectangular prisms, sometimes called cuboids. Look up the definition of a prism online. Something like this will be returned:

A prism is a polyhedron, with two parallel faces called bases. The other faces are always parallelograms. The prism is named by the shape of its base. - Relate the definition to the packets on the desktop.

What does parallel mean? Where are the two parallel faces? (Look for two identical [congruent] faces at opposite ends)

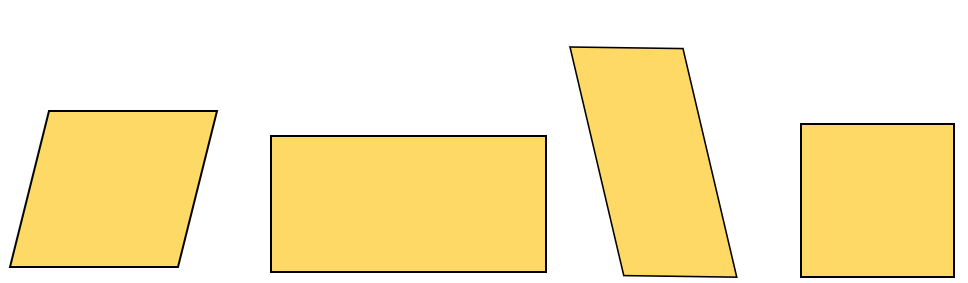

What is a parallelogram? (Quadrilateral with two pairs of parallel opposite sides) - Ask your students to draw three different parallelograms. Try to broaden their view of what shapes are types of parallelograms, including the rhombus, rectangle and square.

- Look at Slide One of PowerPoint 1.

Discuss which of these solids is a type of prism.

Look for students to identify congruent ‘end’ faces (can be base and top) and parallelograms, usually rectangles, wrapping around the sides of the end faces. Prisms are named by the end faces. Slide one has a triangular prism. A cylinder can be classified as a type of prism, though it is the limiting case with an infinite number of rectangular faces.

Also consider the non-examples. Slide One has two pyramids (triangular and cone), curved surfaces (sphere), and some other polyhedra (octahedron and icosahedron). - Discuss why this shape is not a prism. (The end faces are not congruent)

- Come back to the boxes on the desktop.

Your task is to find out the largest number of little cubes each of your five boxes will hold. Label the boxes so you can refer to them. - Show the students a single 1cm3 place value block cube.

What can you tell me about the size of this cube?

You may need to measure the edges of the cube with a ruler to convince them that it is a cubic centimetre. Show them how the unit size can be written as 1 cm3, and said as “one cubic centimetre”.

We write the size of this cube as 1cm3. What does the ‘3’ represent? (the cube is 1cm in all three dimensions, length, height, depth) - Set the students to work in small groups. Each group needs five different packets, a ruler, a calculator, one single place value block cube, and paper to record their working. Ensure students support each other and have opportunities to experience both tuakana and teina roles as they do this. Look for your students to:

- Recognise that the cubes need to be packed tightly to get the largest number in each packet.

- Find more efficient ways to count the number of cubes, e.g. create a layer or stack.

- Measure the edge length to save iterating the unit cube along edges.

- Use multiplication of edge lengths to find the volume of each box in cubic centimetres.

- Apply fraction knowledge to find the volume of parts where the cubes do not fit exactly, i.e. vacant space.

- After an appropriate time, gather the class to have a korero about their strategies. Choose groups that illustrate a progression in sophistication:

Fill and count → Create stacks → Create layers → Multiply whole number edge lengths - Ask students to explain their methods rather than focus on specific answers. You might use Slides Two, Three and Four to discuss how multiplication works to calculate the volume of a rectangular prism. An interesting point of discussion is whether the order of multiplying matters. For Slide Four:

Does 8 x (5 x 5) give the same volume as 5 x (8 x 5)? - Copymaster 1 has some volume problems for students to solve. As students work check to see how they are calculating each volume:

- Is multiplication their preferred method?

- Can they combine multiplication and division to find the missing side lengths?

- Talk with students about the world’s tallest buildings, or the tallest buildings in your local area. While the more recent tall buildings, like the Auckland Skytower, are in thin cylindrical-shaped tower form, some of the older structures are combinations of cuboid shapes. For example, the Sears Tower in Chicago, and the Rialto Tower in Melbourne, are collections of cuboid in structure. Pictures of these buildings are easily found online.

- Tell the students that they are to make a scale model of a tall building by glueing together at least three different cardboard packets from those brought to school. Each building is then glued to a base to form a skyscraper, as seen in large cities throughout the world.

- Allow students time to develop their skyscrapers in groups of four or five. Bring the class back together and discuss what statistics could be displayed about each building. Suggestions might include height, width, length, and volume. Discuss whether naming the dimensions correctly matters (i.e. height, width, length, depth, breadth, etc). Which is which? Does it matter? When naming the dimensions of a three-dimensional figure, the most important thing to remember is make sense and be clear. It is helpful to use labels. To demonstrate this, you could model writing down the different dimensions of a real building from an image (some estimation or research may be required), or focus on the dimensions of one of the scale models.

Invite suggestions about how the volume, in cubic centimetres, might be worked out. Ideas might include building a cuboid of similar size and counting the cubes (successful but inefficient), making one layer of the building, counting the cubes in one layer and using equal additions to make up the height of the building, and multiplying by the edge lengths. Highlight the efficiency of the edge length approach. - Send the students away to label their structures, with stickers in appropriate places, giving the name of the building (eg. The Toa Tower), and the various edge lengths in centimetres. Note that for some packets these lengths may need to be rounded to the nearest centimetre. Monitor the students’ accuracy in measuring to the nearest centimetre.

- When each building is labelled, instruct the students to choose any five buildings from around the room and calculate the volume (office space) of each structure in cubic centimetres. After a time the original creator of each building can calculate its volume and display it using a sticker. Each student can then compare their solutions and discuss discrepancies with the builder.

- The class tries to identify the room’s biggest buildings by height and volume. This data could be displayed in a graph as an extension and a suitable scale (eg. 1cm = 10 m) established to relate the models to their actual size in real life. Note that the scale has interesting implications for volume in cubic metres. A scale of 1cm = 10m will mean that 1 cm3 = 1000 m3 which is a very large space.

Session Two

In this session students attempt “The cereal box challenge”. Their task is to maximise the volume of a cereal box that can be made from A4 sized pieces of 1cm grid paper. You could adapt the learning in this session to reflect the current learning, and/or cultural makeup of your class. For example, instead of a “cereal box challenge” you could pose the problem as designing a pattern for a Wakahuia or Papahou (wooden containers used to hold personal taonga, or treasures).

- Begin with the packets that were used in Session One.

Cardboard packaging is usually created by die cutting a template or net, creasing the template, then folding up the packet. Tabs are glued to hold the packet together. You might find a video online to illustrate the creation of packaging (search “How cardboard boxes are made”).

Sketch what you think the template of your packet would look like before folding and glueing. Be as accurate as you can. You will need to measure the edge lengths of the packet and draw the template the correct size. - Provide pairs of students with a packet, blank A3 sized paper, cellotape, rulers, pencil, and scissors. Let them attempt to recreate the template. Look for students to:

- Use some ‘prototypical’ template for rectangular prism (usually a t shape).

- Accurately measure the lengths of the edges of the packet.

- Transfer the measurements to the correct place on their template.

- Provide tabs in appropriate places and part faces where those parts form the top and bottom of the packet.

- Once students have created a template, they can cut it out, fold it, and tape it. Ask them to compare their template to the original packet, and notice any ways they could improve it.

Does the packet give volume information?

Most packets provide information about net weight, that is the mass of the contents. This can be quite misleading as often the contents are nowhere as much, by volume, as the packet.

Why do the manufacturers only provide weight information?

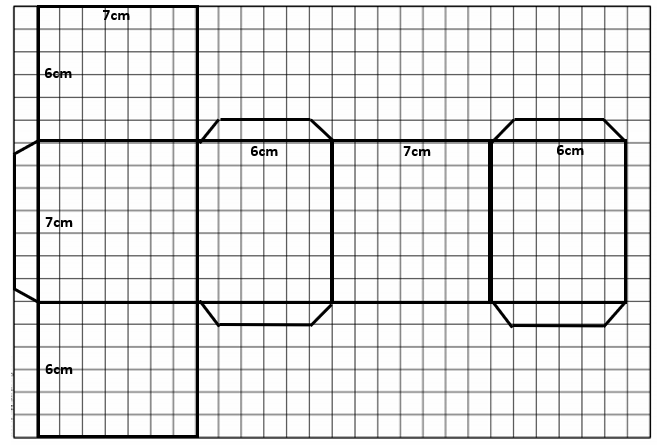

Most contents in packets compress as they settle from the time they were filled. This is particularly true when the packets are transported. Net weight does not change though volume does. - Introduce the challenge using PowerPoint 2. Let students work on pairs to create the box they believe maximises the volume. You might pair students up for increased support, and encourage tuakana-teina, or work with a small group of students to model this activity. Students will need copies of Copymaster 2, rulers, scissors, tapes, and calculators. Look to see if students:

- Minimise the wastage from pieces that are not in the box template.

- Consider how changes to their template increase or decrease the volume.

- Experiment with lengths that are fractions and decimals, e.g. 7.5 cm.

- Recognise that a cuboid as close as possible to a cube is likely to have maximum volume.

- It is important that students record edge lengths on their template, and take a digital photograph as a record before the template is folded and taped. Students can record the volume of their box inside it so the finished products can be ordered by volume.

- After an appropriate time, gather the class to compare the boxes that have been made.

What were some considerations as you found the box with the greatest volume?

Students should discuss how changing an edge affects the length of other edges. They should also acknowledge the constraint of the 19cm x 28cm size of the paper, and how increasing the height of the box decreased the base, and vice versa. You might put three pairs of students together to check the volume calculations (call that volume auditing). - Display the boxes by stapling them to a wall, possibly in order of volume. A winning entry might look like this box that has a volume of 7 x 7 x 6 = 294 cm3.

Some students might also consider the normal shape of a one-serve cereal box and opt for a less regular shape.

Session Three

In this session the problem is based on finding the most efficient way to pack a collection of cuboids (rectangular prisms) into a confined space. This skill has many real-life contexts that you may wish to use as a story shell, including packing the car boot for a holiday or groceries at the supermarket. The context of the NASA first space trip to Mars may create more interest. Space is at a premium on spacecraft and advanced technology is designed to be compact!

- Provide the students with connecting cubes of various colours, they will need their 30cm ruler as well. Instruct them to build the following packets from the cubes. Make each packet a different colour. Note that connecting cubes are 2cm x 2cm x 2cm.

- 4 cm x 4 cm x 6 cm

- 2 cm x 8 cm x 6 cm

- 6 cm x 6 cm x 4 cm

- 2 cm x 6 cm x 4 cm

- Their task as the NASA engineer is to find a way of putting the parcels together in the most compact way possible. Allow the students time to attempt the problem. Stress (i) the need to record their solutions and (ii) that they should not join the packets together so that they can be unpacked if they haven’t been joined together correctly. Arranging the packets by manipulation is quite easy.

- Ask the students to work out the total number of cubes used. This creates an interesting crosscheck where the number of cubes in the combined cuboid can be checked against the sum of the cubes in the four packets. Ask the students how knowing the total volume of the combined cuboid could help in arranging the packages in a more difficult problem of this type. In this example the total volume is 48 connecting cubes (384 cm3) so that limits the dimensions of the cuboid (e.g. 4 x 6 x 2, 3 x 4 x 4).

- Challenge:

Tell the students to:- Choose one of the packets they used in Session One. It must have edges that are whole numbers of centimetres and be as big as possible.

- Make up a set of up to six cuboids, using different colours, that will fit exactly inside the packet they have chosen.

- Record a solution to their problem in some way. Isometric drawing is a good method (see Copymaster 3). Students could explore isometric drawing in more detail using the Little Boxes activity if necessary.

- Give their problem to another group of students to solve.

- After the students have attempted a few problems, gather the class to have a korero about possible strategies. Many students will use trial and error approaches, but some may be more systematic. Did they:

- Record the dimensions of each cuboid multiplicatively, e.g. 2 x 3 x 4.

- Measure the box and calculate the total number of connecting cubes needed.

- Compare the edge lengths with the dimensions of each cuboid. (This can eliminate or confirm the locations of some cuboids)

- The final problem is about a growing cuboid pattern. Give the students Copymaster 4. Calculators will be needed as the volumes get quite large. You might get a few students to build the cuboids so they can be referred to.

Students are likely to begin by calculating the volumes of the first three buildings and arranging the data in a table:

Building 1 2 3 Volume 6 24 60 - They are unlikely to make much progress by looking at differences in the table. Instead they should focus on what changes as the pattern increases. Each dimension increases by one and depth is always the pattern number. Width is one more than the pattern number, and height is two more. In general, the volume can be calculated as n x (n + 1) x (n + 2), where n is the pattern number.

- The final question can be attempted by trial and improvement. However, it is more efficient to consider that n x n x n will be a bit less than 7890. N x n x n is the same as ‘n cubed’ so students could use a scientific calculator, e.g. 203 = 20 x 20 x 20 = 8 000. Therefore, n must be a little less than 20. 19 x 20 x 21 = 7890 so n is 19, meaning 7890 is the volume of the 19th building.

Session Four

Problem One:

- Show the students Slide One of PowerPoint 3.

What does ‘L’ mean when referring to a backpack or chilly bin?

Students may be familiar with L referring to the unit of capacity, the litre.

Surely that does not mean that the backpack is going to be filled with water. Why is the litre used as the unit?

The use of litre means that the measure is referring to the capacity of the backpack or chilly bin. Capacity is how much a container holds and usually refers to amounts of liquid or gas. - Hold up a 1 litre milk carton.

This is a one litre container. Estimate how many cubic centimetres are equivalent to one litre. - Let your students estimate then measure the dimensions of the cuboid section of the one litre carton. The dimensions are usually; height (22cm), length (7cm), depth (7cm). Since 7 x 7 x 49 = 1078 cm3 which include air space. The actual volume of one litre is 1000 cm3.

- Present a set of place value blocks.

Who can make up the volume of one litre?

Students should recognise that gathering 1000 unit cube will be tiresome, and collect bigger units, such as flats that represent 100cm3. Ten flats have a combined volume of 1000cm3 and form a cube that is 10cm x 10cm x 10cm. If you have a large place value block cube that represents 1000cm3 you might present it then. - The capacity of a backpack is the volume when it is completely full. Your task now is to work out the capacity of your school bag in litres.

Students will need rulers and calculators to work out the capacity of their school bag. Encourage them to record their calculations so that it can be verified. After a suitable time, gather the class to discuss what they found out.

What is the average bag capacity for students in our class?

Problem Two:

- Pose this problem (see Slide Two of PowerPoint 3).

The Just Juice Company wants a new carton that will hold exactly 330 mL of juice. Each edge of the new carton must be an exact number of centimetres long (e.g. it cannot be 4.75 cm long).

One possible carton would be 330 cm x 1 cm x 1 cm. Ask the students to imagine what that would look like and how we know it would hold 330mL. Suggest that this carton would not be very practical and invite them to design other cartons which are more appropriate. - The students can make their cartons from centimetre squared paper if needed but encourage them to use their knowledge of volume to solve the problem efficiently. Issues such as the ease of fit in a person’s hand should be considered.

Allow the students time to find several possible cartons and bring the class together to share their ideas. Focus on their use of the cuboid volume formula (width x breadth x height) and the application of factors in finding workable dimensions. For example, if 10 cm is to be the length of one edge then 330 ÷ 10 = 33 gives the product of the other two edge lengths. Therefore 10 x 3 x 11 are the dimensions of one possible carton. The possible carton sizes could be entered in a table, in a systematic way, to check if all possible cartons have been found. Spreadsheet formulae could be used to make calculations easier:

Edge One (cm) Edge Two (cm) Edge Three (cm) Volume (cm3) 1 1 330 330 1 2 165 330 1 3 110 330 1 5 66 330 1 6 55 330 1 10 33 330 1 11 30 330 1 15 22 330 2 3 55 330 2 5 33 330 2 11 15 330 3 5 22 330 3 10 11 330 5 11 6 330 - Decide as a class on the most suitable dimensions. You might compare the class solution to actual dimensions of a small juice carton.

Other possible extension problems:

- What different cuboids can be made with a volume of 180 connecting cubes?

Which of those cuboids is most compact? Explain why.

- Make a cuboid from connecting cubes that has dimensions of 2 x 3 x 4.

Now make the cuboid that has each dimension doubled, that is, 4 x 6 x 8.

When the edges are doubled in length what is the effect on volume?

How does volume increase if you treble or quadruple edge length?

Investigate, and explain why this happens.

Dear family and whānau,

This week we have been looking at box shapes (cuboids). We can think of measuring the edges of a box to get the length, height, and depth. From those measures we can work out the volume of the box, possibly in units such as cubic centimetres.

Discuss with your student how they would find the volume of a box that you have at home.